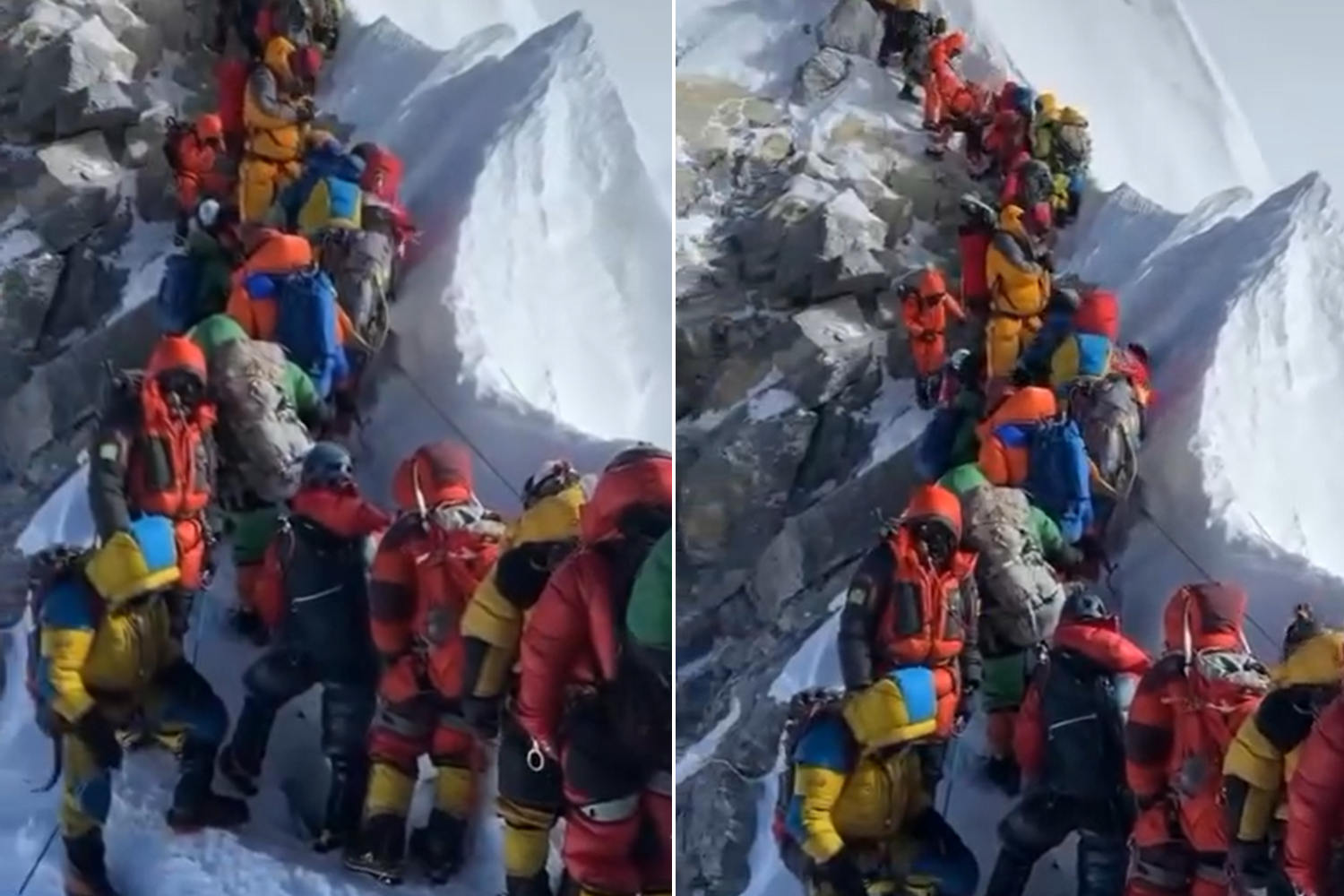

Everest is no longer just a mountain to climb—it's a crowded queue at 29,000 feet, with deadly consequences for both people and planet.

@Asiana Nepal Treks & Expedition Pvt. Ltd/Facebook

Every year, more and more people line up—literally—to conquer Mount Everest, the world’s tallest peak rising on the border between Nepal and Tibet. The sight of climbers jammed shoulder to shoulder at over 29,000 feet (8,800 meters) is no longer shocking. If anything, it’s become expected—a symbol of an issue that is spiraling out of control.

As of mid-2025, over 100 ascents have already been completed. But with each new season, the dangers linked to extreme overcrowding on the mountain grow more apparent—and more deadly.

Breaking the unwritten rules above the clouds

A recent video shared by Asiana Nepal Treks captured a disturbing moment: climbers on their way down refused to yield to those ascending. It might seem trivial, but in the thin air of Everest, that’s a violation of a life-saving, unwritten rule. The mountain has its own etiquette, forged not by culture but by necessity. When that breaks down, so does safety.

Up there, every misstep isn’t just careless—it can be catastrophic.

The death zone and the price of standing still

Above 25,000 feet (7,600 meters), climbers enter the infamous death zone, where the oxygen level is so low the human body starts to shut down. The environment is brutally hostile. Breathing becomes an effort, judgment falters, and even the simplest decisions can spiral into disaster.

Getting stuck in a traffic jam at that altitude means wasting oxygen just to stand still. It’s not only the ascent that’s delayed—the descent becomes just as treacherous. Pausing too long in sub-zero temperatures can lead to hypothermia, high-altitude pulmonary edema, or worse, fatal altitude sickness.

Mount Everest is already littered with more than 200 frozen bodies, many of them unrecoverable, a grim reminder of how unforgiving the mountain can be. As one climber put it, “Sembrava di fare lo slalom tra i corpi imbalsamati.” Like weaving through a macabre slalom course of mummified corpses.

Selfie culture on the roof of the world

But perhaps the most chilling truth isn’t in the temperature. It’s in the mindset. What used to be a nearly mythical feat is now treated by some as just another adventure to cross off the bucket list.

Guides have reported climbers stopping mid-ascent for selfies, barely aware of where they are. “C’è chi si ferma a farsi i selfie senza sapere nemmeno dove si trova,” one guide remarked. The climb has morphed into mass tourism, with scores of underprepared amateurs queuing up during the few narrow weather windows of the year.

Some pay over $45,000 (€42,000) for the chance to reach the summit. But money doesn’t buy skill, or altitude conditioning. And that disconnect is proving dangerous for everyone on the mountain.

The mountain that’s drowning in trash

The damage isn’t just human. Everest’s delicate environment is under siege. The overcrowding has left behind a toxic trail of plastic, gear, and even human waste—which doesn’t decompose at those altitudes. What’s left behind doesn’t just ruin the mountain’s integrity; it also poses health risks for local communities downstream.

Faced with this growing crisis, the Supreme Court of Nepal has intervened, urging limits on the number of climbing permits issued. It’s a rare move, but one that reflects growing concern over a phenomenon that’s drifting into ecological and ethical absurdity.

Because in the race to touch the sky, Everest is starting to fall apart at the base.

Journey to the Top of the world: mount Everest

Posted by Asiana Nepal Treks & Expedition Pvt. Ltd. on Tuesday, June 3, 2025