Brazilian ranchers in Pará and Rondônia say that JBS, the world's largest beef company, cannot currently achieve its stated goal of deforestation-free cattle.

@Animal Equality

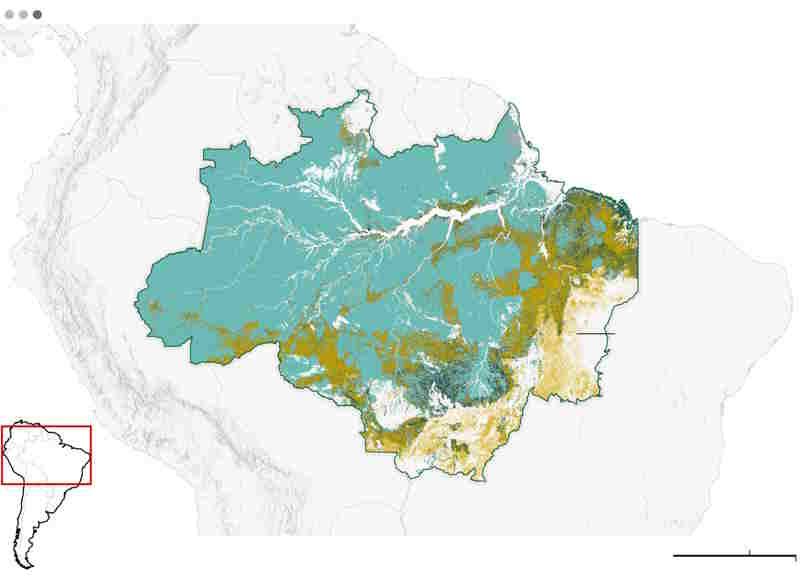

Beef production continues to fuel Amazon deforestation, despite corporate promises and international scrutiny. Cattle ranching remains the main driver behind tree loss in the rainforest, and scientists warn that this destruction is pushing the Amazon toward a tipping point—one where it could shift from a carbon sink to a carbon source.

JBS, the Brazilian meatpacking giant that dominates the global beef market, pledged to clean up its Amazon supply chain by the end of 2025.

But that promise is far from reality.

A joint investigation by The Guardian, Unearthed, and Repórter Brasil interviewed over 35 people, including ranchers and union leaders representing thousands of farms in Pará and Rondônia.

Their findings suggest that JBS is actively dodging controls and ignoring environmental agreements. Most of those interviewed do not believe the company will meet its core environmental commitment: to eliminate deforestation from its beef supply chain.

To do so, JBS would need to sever ties with all direct and indirect suppliers linked to land clearance. The company set its own deadline for this target: December 2025.

“They say they’ll make it, but I’m telling you—it’s impossible”

This is how one rancher described JBS’s claim that it will halt deforestation completely. The skepticism runs deep among local farmers.

JBS’s weak defense

“Drawing conclusions from a limited sample of 30 farmers while ignoring that JBS has over 40,000 registered suppliers is completely irresponsible”

That was the company’s official response to the investigation.

To meet its targets, JBS says it must register all direct and indirect suppliers and ensure that none of the beef it sources from the Amazon comes from cattle raised on deforested land.

It has set up “green offices” offering free consultancy to ranchers for a 3–6 month compliance process, which includes planting trees, withdrawing from disputed territories, or conducting other environmental recovery work. These details are then entered into a JBS database, which is supposed to track farms and alert them when they fall short of compliance.

In Pará, the company is also working with the state government on a tagging system that would track the state’s entire herd of 57 million pounds of cattle by 2026.

But the investigation found serious loopholes. Several indirect suppliers admitted to using middlemen to “clean” the environmental footprint of their cattle. New traceability systems can be sidestepped by slaughtering cattle elsewhere and selling only the meat—not the live animals—to JBS or other buyers.

History repeats itself

JBS has a well-documented track record of environmental violations. Last year, it was again linked to Amazon deforestation.

New York Attorney General Letitia James filed a lawsuit accusing JBS of misleading consumers about its climate goals to boost sales. Meanwhile, a bipartisan group of 15 U.S. senators urged the SEC to reject JBS’s stock listing request.

“Dozens of journalistic and NGO reports have shown that JBS is linked to forest and ecosystem destruction more than any other company in Brazil,”

states an open letter.

And the damage is visible everywhere.