A mysterious skull discovered in Greece rewrites history: Neanderthals weren't the only ones in Europe 286,000 years ago.

Table of contents

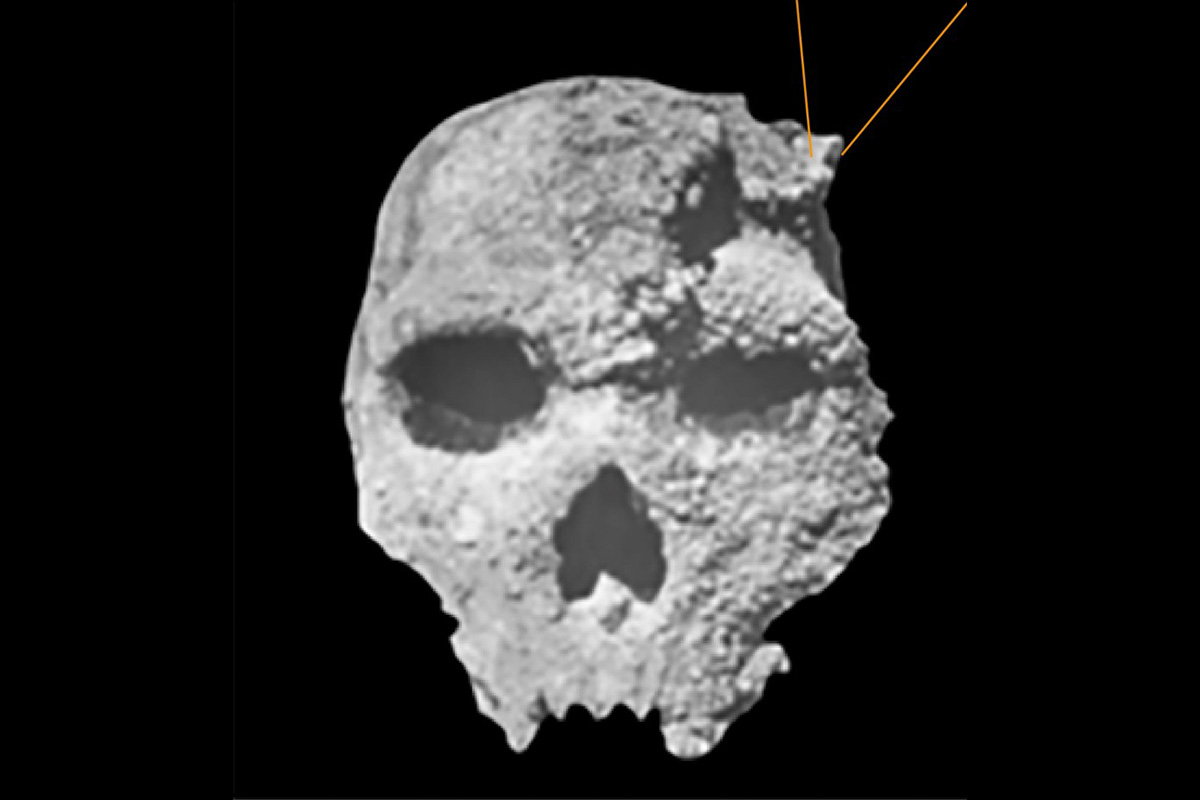

For more than six decades, a mysterious skull found in a Greek cave has puzzled scientists around the world. Now, new research has provided important clues that could reshape our understanding of human evolution in Europe. The Petralona skull, discovered in 1960, belonged to an ancient human species distinct from both Neanderthals and modern humans—suggesting that our prehistoric relatives weren’t the only human inhabitants of Europe during the Middle Pleistocene period.

A 286,000-year-old enigma finally dated

The nearly complete cranium from Petralona Cave in northern Greece has long sparked debate. Clearly part of the Homo genus, it displays features that don’t fit neatly with either Neanderthals or Homo sapiens. The biggest challenge has been determining its age: previous estimates ranged from 170,000 to 700,000 years, a gap too wide to draw meaningful conclusions.

Now, a research team from France’s Institut de Paléontologie Humaine has applied advanced uranium-series dating techniques, establishing that the skull is at least 286,000 years old, with a margin of error of around 9,000 years. The findings, published in the Journal of Human Evolution, finally provide the precision needed to place the fossil within Europe’s complex evolutionary story.

Paleoanthropologist Chris Stringer of London’s Natural History Museum explains: the fossil is “distinct from H. sapiens and Neanderthals,” and the new age estimate supports the idea that “this population coexisted with the evolving Neanderthal lineage in the later Middle Pleistocene of Europe.”

Decoding the cave’s geological clock

The breakthrough came through uranium-series (U-series) dating, a method based on the predictable radioactive decay of uranium into thorium within mineral deposits. Unlike traditional dating techniques that struggle with ancient cave fossils, this approach measures calcite layers that formed directly on the skull.

When water seeped into the cave walls, it carried uranium but left thorium behind. As uranium decayed over thousands of years, it created a reliable chronological marker. By analyzing both the calcite coating on the cranium and deposits across different parts of the cave, researchers were able to confirm a minimum age of 286,000 years and reconstruct aspects of the cave’s geological history.

Interestingly, they found that the calcite covering the skull wasn’t contemporary with the cave wall deposits, suggesting that the fossil’s placement in the chamber was more complex than previously thought.

Not quite Neanderthal, not quite modern human

What makes the Petralona skull so intriguing isn’t only its age but its unique morphology. Likely belonging to a young adult male, the cranium shows robust brow ridges and a broad face, yet its brain capacity falls between earlier Homo species and later Neanderthals.

It’s neither primitive enough to be Homo erectus nor advanced enough to be a clear Neanderthal ancestor. Many researchers see it as part of Homo heidelbergensis or a closely related lineage—an evolutionary branch that developed parallel to the ancestors of Neanderthals.

This highlights a broader pattern: human evolution in Europe was not a simple, linear march but a mosaic of populations, some of which may have contributed to later species, while others left no genetic trace.

Europe’s crowded prehistoric landscape

The new dating places the Petralona skull within a period when multiple human groups likely shared Europe. Some were evolving toward Neanderthals, others followed different evolutionary paths, and interbreeding may have occurred. Rather than one dominant lineage, the continent appears to have hosted a patchwork of human relatives, shaped by climate change and shifting environments.

The fossil’s original stratigraphic position remains uncertain, adding to the mystery. But what’s clear is that this individual lived during the later Middle Pleistocene, a key moment in the evolutionary story of our genus.

From discovery to new perspectives

The skull was first uncovered in 1960 by villager Christos Sarigiannidis, about 30 cm (12 inches) above the cave floor. Since then, it has been at the center of scientific study, political disputes, and legal battles over excavation rights. The Petralona Cave itself was reopened to the public in 2024 after restoration, and research continues under the oversight of the Hellenic Ministry of Culture.

A bigger picture of human evolution

The Petralona skull joins a growing number of European finds challenging the idea of a simple evolutionary path. Fossils from Germany, Italy, England, and Spain also suggest that Europe was home to diverse populations far earlier than once believed.

Together, these discoveries paint prehistoric Europe as a crossroads of human evolution, where different lineages coexisted, adapted, and sometimes vanished. Each fossil—whether Petralona, the Denisovans, or others yet to be classified—adds a piece to an increasingly complex puzzle.

What emerges is a reminder: the road to modern humanity was neither straight nor simple. The Petralona skull is just one thread in a vast tapestry, offering a glimpse into forgotten worlds and the remarkable diversity of our ancient relatives.

Source: Journal of Human Evolution