For centuries, students with learning differences were dismissed as “lazy.” Yet many geniuses, from Leonardo da Vinci to Agatha Christie, likely had SLD. Their stories reveal the power of cognitive diversity.

Table of contents

For decades, children who struggled to read, write, or do math were dismissed with humiliating labels: “lazy,” “distracted,” “unmotivated.” Today, we know that many of those students simply had what are now called Specific Learning Disorders (SLD) — conditions such as dyslexia, dysgraphia, dysorthographia, or dyscalculia.

These challenges have nothing to do with intelligence. They’re about different ways of processing information, ways that schools were often unable—or unwilling—to recognize. As a result, brilliant minds were sometimes sidelined, their potential quietly suffocated by misunderstanding. And yet, history has a way of revealing its secrets. Look closely, and you’ll find that some of humanity’s greatest geniuses would almost certainly receive an SLD diagnosis today.

Let’s look at a few remarkable figures who were underestimated by their schools, but left a lasting mark on science, art, and literature.

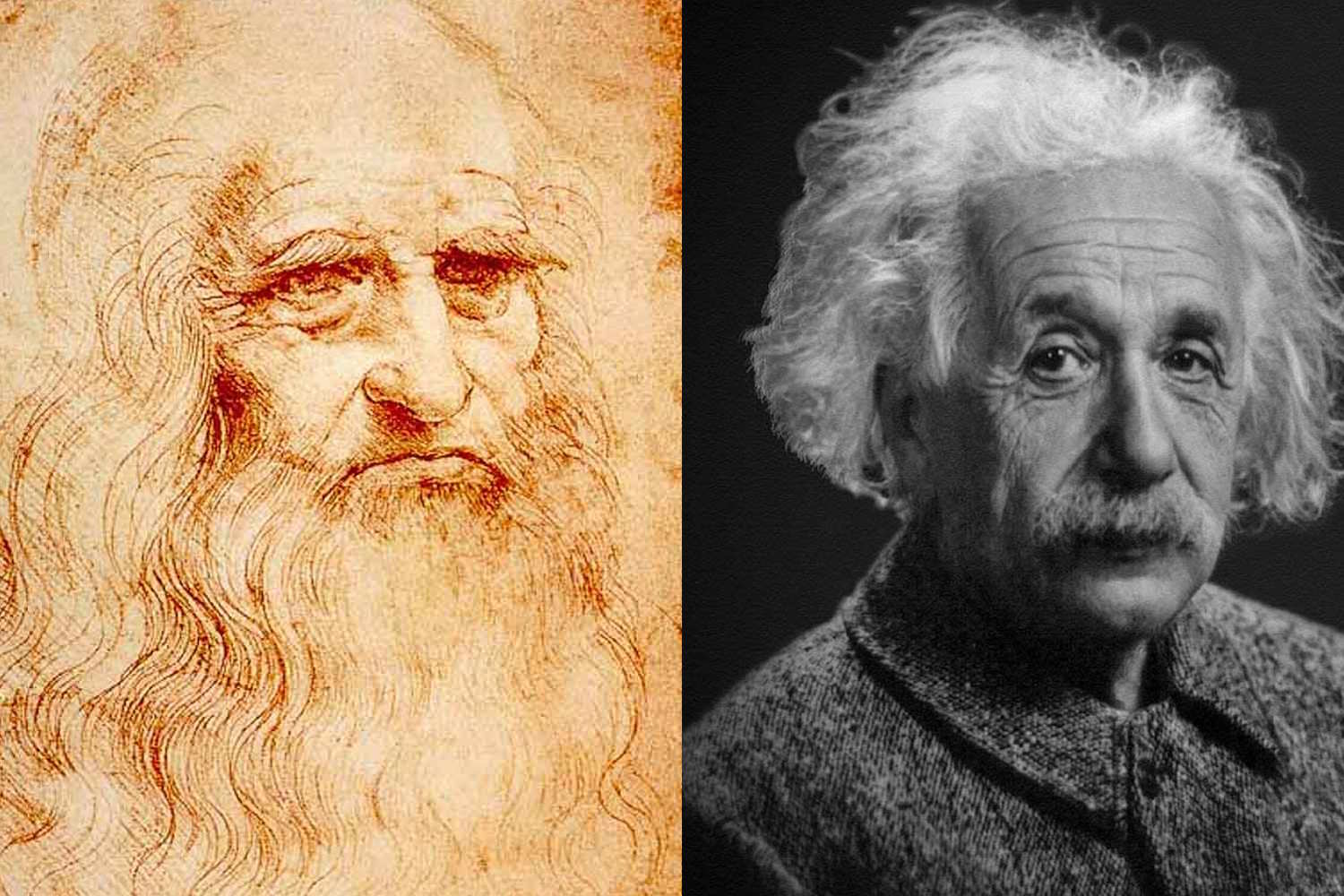

Leonardo da Vinci: the visual genius who wrote backwards

Leonardo da Vinci remains one of the most captivating examples. His notebooks are filled with spelling mistakes, irregular handwriting, and mirror writing, flowing from right to left. Several scholars have suggested that Leonardo displayed signs consistent with dyslexia and dysgraphia.

According to Marco Catani and Paolo Mazzarello (Brain, 2019), Leonardo also showed traits associated with ADHD, such as struggling to finish projects and having a scattershot attention span across countless interests.

Had he been judged solely by his linguistic abilities, Leonardo might never have become the universal symbol of creative genius that he is today. It’s a sobering thought.

Hans Christian andersen: the storyteller who invented words

The author of The Little Mermaid and The Ugly Duckling left behind manuscripts riddled with phonetic and spelling errors. He sometimes invented entirely new words, while at other times he repeatedly misspelled common ones.

These characteristics are typical of dyslexia, but Andersen found his strength in imagination and narrative. His difficulties didn’t hold him back; they became part of the texture of his storytelling, which continues to enchant readers centuries later.

Albert Einstein: the visual thinker

The legend that Albert Einstein was a “bad student” is exaggerated, but it’s true that he had linguistic delays and was slower with verbal processing. Some biographers have suggested he showed dyslexic traits, particularly in reading aloud and writing.

Einstein thought in pictures and abstract concepts, not in words. This unconventional cognitive style helped him revolutionize physics, overturning the scientific paradigms of his time with startling originality.

It’s almost poetic that a man who struggled with traditional language reshaped the language of the universe itself.

Pablo Picasso: words held him back, art set him free

Pablo Picasso struggled with reading and writing and clashed with the discipline of school life. But when it came to painting, he found a liberating language that needed no translation.

Many scholars believe he displayed dyslexic traits, yet this was never a limitation. Quite the opposite: Picasso’s visual creativity and rule-breaking transformed 20th-century art, forever changing how we see the world.

Agatha Christie: the writer who preferred to dictate

Agatha Christie, the undisputed queen of mystery, hated rereading her own work. Her manuscripts were often peppered with spelling mistakes, and she frequently dictated her novels to secretaries.

Experts point to possible dysgraphic or dyslexic difficulties. But that didn’t stop her from becoming one of the most widely read and translated authors in the world. She’s living proof that storytelling brilliance can flourish far beyond the boundaries of formal accuracy.

Misunderstood geniuses then, students with sld today

The stories of these figures remind us of something simple yet essential: academic struggles do not define intelligence. Cognitive diversity is a resource, not a defect. And early diagnosis, combined with the right support, can change a child’s life.

Many of these geniuses achieved greatness despite the educational systems of their time. Today, thanks to growing awareness of SLD, we have the chance to build schools that don’t label students—but empower them.