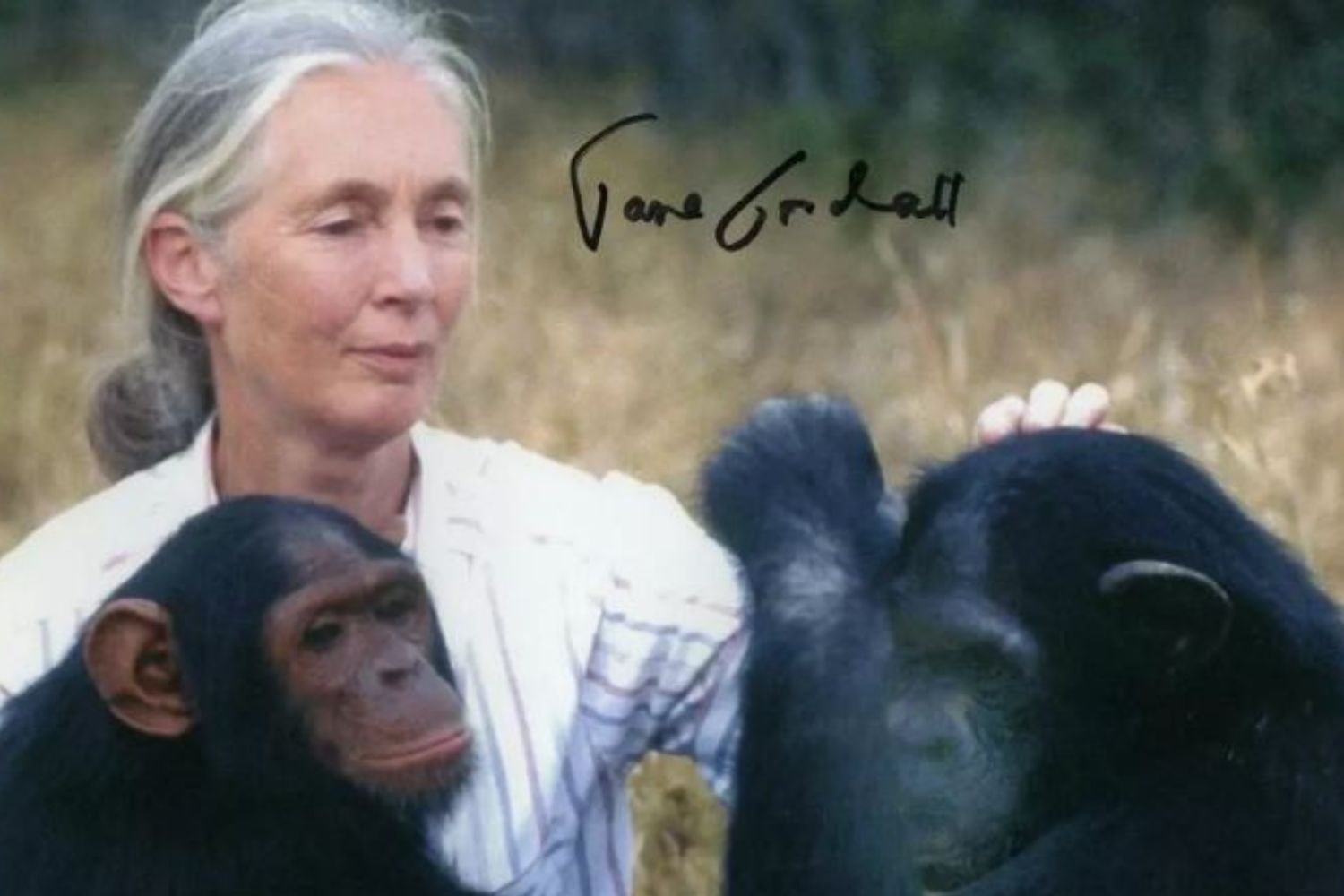

Jane Goodall’s journey from curious young woman to global icon transformed both science and our relationship with the natural world. Her empathy built a bridge between species.

@Jane Goodall Institute

Some people alter the course of human thought forever. Jane Goodall was one of them.

I picture her in 1960, a young woman stepping off a small boat onto the shores of Lake Tanganyika in what is now Tanzania. She carried almost nothing with her—just a worn notebook, a second-hand pair of binoculars, and a boundless curiosity that would end up transforming science itself. She had no degree, no formal credentials. The academic world at the time would have dismissed her as unqualified. What she did have were two tools more powerful than any diploma: infinite patience and radical empathy.

Listening before speaking

Her mission sounded deceptively simple: observe wild chimpanzees and learn from them. It was entrusted to her by Louis Leakey, the legendary paleoanthropologist who deliberately chose Jane, then working as a secretary, for her “unclouded mind.” He wanted someone free from the rigid scientific dogma of the 1950s, a dogma that saw animals as little more than instinct-driven machines, catalogued coldly with numbers and detached observation.

And so Jane began to watch. For months, the chimpanzees fled at the first sign of her presence. She didn’t chase them. She waited. Day after day, she sat quietly in the same spot, letting the forest accept her. Her presence became part of the background, as ordinary as the rustling of leaves. This wasn’t passive waiting; it was a silent dialogue built on respect. Eventually, the chimpanzees let her in. That’s when everything changed.

David Greybeard and the end of certainty

Where science had seen only “subject B7,” Jane saw David Greybeard, the first chimpanzee to trust her. He was also the first to reveal something that would shake the foundations of anthropology: he used tools. She watched him carefully strip blades of grass, slide them into termite mounds, and pull them out covered with insects—fishing for termites. This single moment, scribbled into her notebook, forced the world to redefine the very idea of what it means to be “human.” If chimpanzees could make and use tools, then humanity was no longer the only species that shaped the environment intentionally.

Naming, observing, understanding

Jane didn’t stop at observation. She named each chimpanzee: Flo, the matriarch; Fifi, her playful daughter; Figan, ambitious and aggressive. By naming them, she shattered the barrier between “object of study” and “individual being.” She revealed their intricate social worlds: shifting alliances, tender maternal care, childish games, political scheming, and, yes, brutal intergroup violence—including acts of cannibalism that stunned researchers. What emerged wasn’t an idyllic Eden or a meaningless chaos, but a complex society eerily similar to our own.

When Jane looked into a chimpanzee’s eyes, she saw—and showed us—a mirror. She dismantled the wall that separated Homo sapiens from the rest of the animal kingdom and replaced it with a bridge. If today the natural world feels a little closer, a little more like home, we owe much of that to her: the young woman who dared to look at animals and see persons.

The activist is born

Jane’s story didn’t end with discovery; in many ways, that was only the beginning. In 1986, at a scientific conference, she pieced together data from across Africa and grasped the scale of destruction: deforestation and poaching were erasing chimpanzee habitats at a terrifying pace. As she later recalled, “I went in as a scientist and came out as an activist.”

She never stopped after that. She traveled the world, carrying her message from lecture halls to village schools. She understood something crucial: you can’t save chimpanzees without helping the people who share their land. Conservation had to go hand in hand with education and the fight against poverty.

Building a home for a movement

This mission needed a structure. In 1977, alongside Genevieve di San Faustino, she founded the Jane Goodall Institute. It wasn’t just another NGO; it was the embodiment of her philosophy. Its work combined scientific research, habitat protection in collaboration with local communities, and—perhaps most importantly—the training of new generations of conscious young leaders. Her talks, whether on prestigious stages or under the tin roofs of rural schools, became almost spiritual encounters, her quiet determination moving people in ways statistics never could.

Understand, care, help

Her greatest lesson can be summed up in one deceptively simple sequence:

Only if we understand can we care. Only if we care will we help. Only if we help shall all be saved.

Understanding, as she showed us, begins with empathetic observation. Care flows naturally from that understanding. And help is the inevitable, active consequence of care.

A living legacy

Her legacy isn’t confined to ethology textbooks. It lives on in millions of young people involved in Roots & Shoots, her global program that empowers youth to create projects for people, animals, and the environment. Her unwavering defense of hope—not passive optimism, but rolled-up-sleeves hope—continues to inspire a planet in crisis.

Thank you, Jane, for opening our eyes. Thank you for reminding us that the greatest changes begin with the simplest, most radical act: looking at another being and recognizing a fellow traveler on this fragile, precious planet.