A microbiology student at WVU discovers a long-sought fungus in morning glory seeds—potentially revolutionizing modern medicine.

@Wikipedia

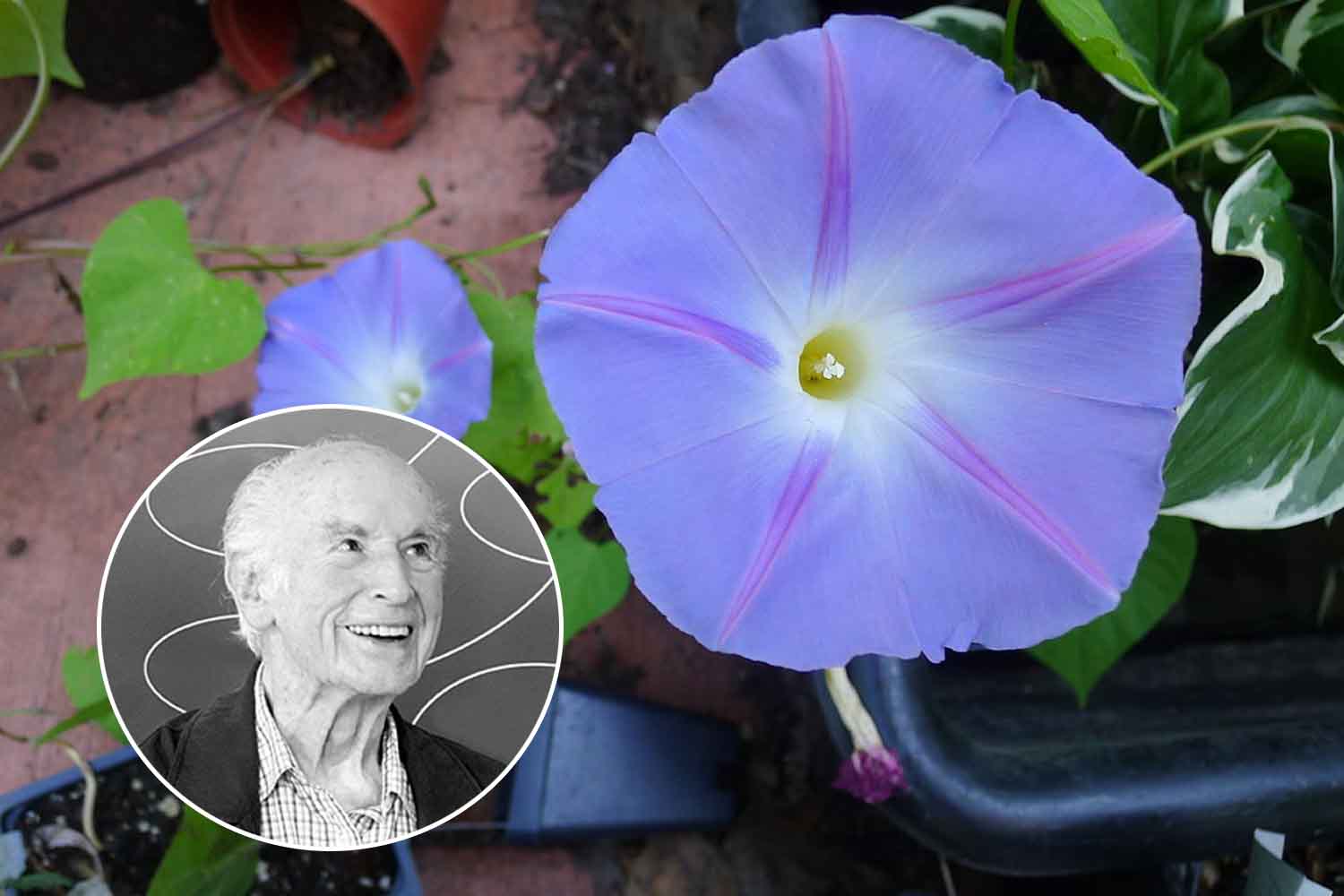

At a lab tucked inside West Virginia University (WVU), an ordinary observation led to an extraordinary discovery. Environmental microbiology student Corinne Hazel was analyzing seeds of Ipomoea, commonly known as morning glory, in search of protective chemical compounds. Nothing suggested that history was about to be made—until she spotted something curious clinging to a seed coat: a faint white fuzz.

That seemingly insignificant hair-like layer turned out to be anything but ordinary. Nestled in its fibers was a previously unidentified fungus—the very organism that Albert Hofmann, the legendary Swiss chemist who first synthesized LSD, had been searching for nearly a century ago. Hofmann had long suspected that morning glory plants harbored a symbiotic lifeform responsible for producing LSD-like compounds. But despite decades of research, the organism had remained elusive.

Until now.

Decoding the secret of periglandula clandestina

Hazel named the newly discovered species Periglandula clandestina, a nod to its secretive, hidden nature. Working with her mentor, Professor Daniel Panaccione, a plant pathology expert, she extracted and sequenced the fungus’s DNA. What they found was a scientific confirmation of Hofmann’s hunch—and the dream of generations of chemists and botanists.

The fungus produces ergot alkaloids, bioactive compounds closely related to those that Hofmann used to synthesize LSD. Panaccione summed it up with admiration:

“Sequencing a genome is already an accomplishment. For a student to do it—especially with a discovery like this—is truly exceptional.”

And it is. Ergot alkaloids are powerful substances. In high doses, they can be toxic, but when carefully manipulated, they have immense pharmaceutical value. They’re already used to treat migraines, manage bleeding disorders, and even play a role in addressing neurological conditions like Parkinson’s disease.

But the implications of this discovery stretch beyond what’s already known. Periglandula clandestina may be able to produce these compounds more efficiently, and in larger quantities, than current synthetic or natural sources. In other words, we could be on the verge of safer, more targeted medications—all thanks to a fungus hiding in a seed.

From accident to breakthrough

Hazel admits that the discovery began with sheer observation and a touch of serendipity:

“We had tons of plants in the lab, and the seeds had these little fuzzy hairs. That’s where we found it. I’m very proud of the work we’ve done at WVU.”

She is now attempting to cultivate the fungus, which grows slowly and demands patience. But more intriguing is the broader question: Are there other symbiotic fungi like this one hiding in other morning glory species? The answer could open up a new chapter in the exploration of endophytic psychedelic fungi—a field that is still in its infancy.

Panaccione reflects:

“This is a perfect example of students recognizing opportunity, rising to the challenge with intelligence, and conducting research at the highest level.”

And to think it all began with a tiny seed and a little white fuzz. Sometimes, that’s all it takes to spark a scientific revolution.

Source: Mycologia