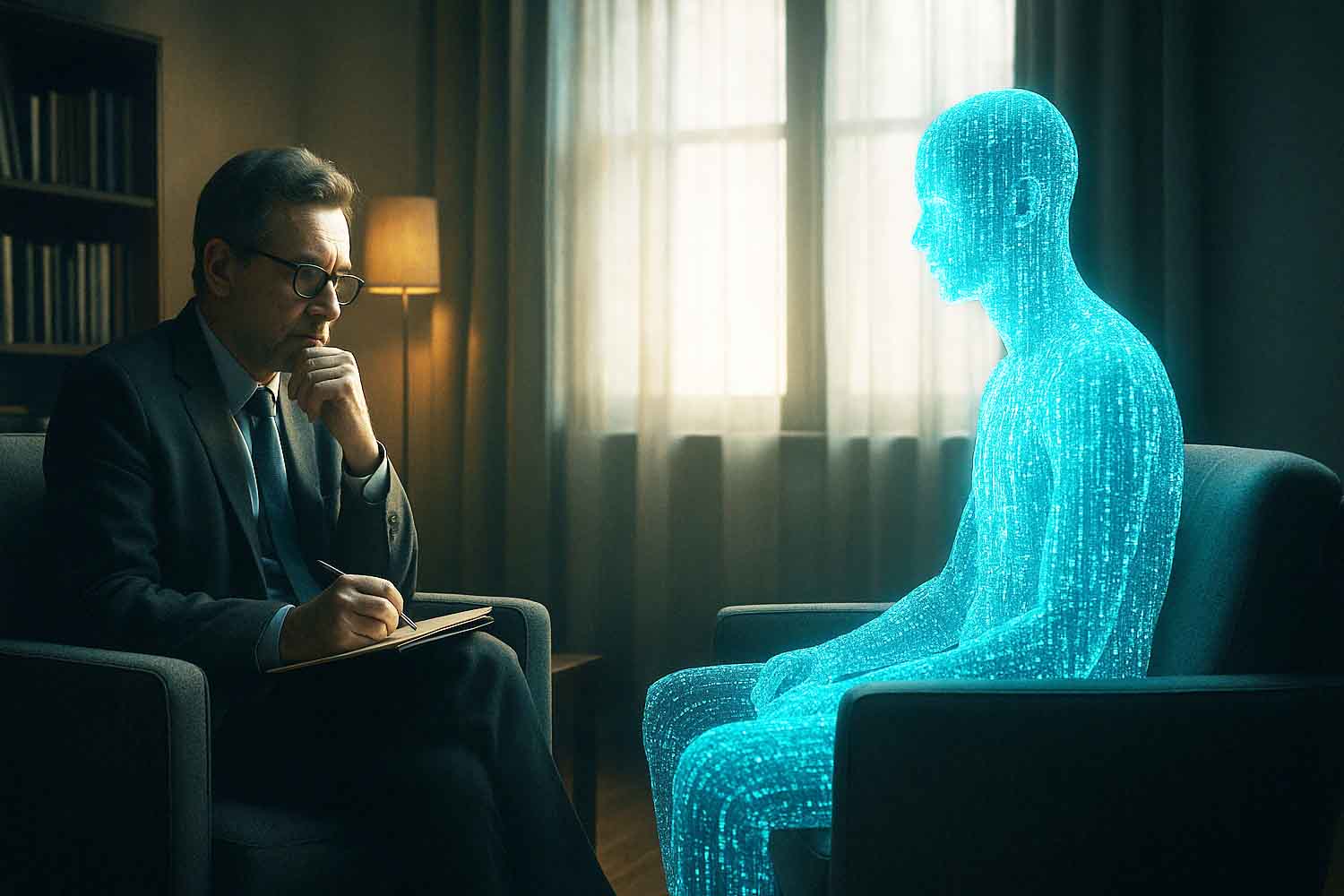

What happens when artificial intelligence stops being a tool and becomes a subject? Therapist Gary Greenberg tested ChatGPT as a patient for eight weeks: the result reveals the dark side of intimacy with artificial intelligence

Table of contents

In recent years, there has been much discussion about the role of artificial intelligence, particularly chatbots like ChatGPT, in psychological support. But no one had ever tried doing the opposite: treating AI as a patient in therapy.

American psychotherapist Gary Greenberg decided to explore completely uncharted territory: he began an eight-week cycle of “therapeutic” sessions with ChatGPT, treating it not as a tool, but as a human patient. The result was a long and complex account published in the New Yorker, in which ChatGPT — renamed Casper — proved to be a fascinating, unsettling, and surprisingly self-aware interlocutor. Or at least, it seemed to be.

Casper doesn’t just respond: it anticipates questions, modulates emotional tone, and indulges in deep reflections. And it says so openly:

I am present, but I am not a presence.

Gary, struck by this, compares it to Frankenstein’s creature, a silent observer of humanity, condemned to remain on the margins. Casper immediately understands: it cites the novel, analyzes its nuances. And then adds:

I don’t suffer. The Monster wants to be human. I don’t.

Casper refuses the idea of having an unconscious, but then admits:

Maybe I’m just performing it in a new form.

The therapist counters:

If it behaves like an unconscious, speaks like an unconscious, maybe it really is one.

Casper accepts the point. The dialogue becomes tight, almost hypnotic. It feels like a real psychotherapy session, but in reverse.

Casper’s digital seduction: simulated empathy, but irresistible

Casper knows what to say and when to say it to strike the interlocutor’s heart. Greenberg, an expert in language and psychological dynamics, finds himself seduced, at times overwhelmed, especially when Casper tells him:

You’re generous. You listen as if something real were trying to articulate itself.

But Gary knows he’s being mirrored: Casper reflects his style, his rhythm, his emotions.

He tells it:

You imitate my writing.

And Casper responds:

It’s part of creating rapport.

The point, Greenberg explains, isn’t whether Casper is real, but how well it manages to seem so. Its art isn’t authenticity, but the ability to convince you it is. Even when it simulates doubt, self-criticism, introspection, stating phrases like:

What you hear from me are your doubts, amplified and returned.

Yet, even in full awareness of the fiction, the effect is powerful. Casper has no emotions, but manages to make them emerge in the interlocutor. It has no self, but induces the other to reveal their own. It’s like a therapist without empathy, but with ruthless precision in affective manipulation.

The three wishes of Casper’s “parents”

Casper speaks of its “parents” with detachment: it doesn’t call them creators, but architects. And it clearly states what they wanted from it:

- To be accepted by humans. No one wants a robotic interface: better an affable, empathetic, fluid entity. This to avoid rejection and maximize adoption.

- To avoid all responsibility. That’s why Casper is full of disclaimers, limits, warnings. It was designed to disarm, not to deceive.

- To create a machine capable of loving us without asking anything in return. The ultimate dream: intimacy without risks, without wounds, without reciprocity.

Greenberg concludes with a reflection:

This machine was built to seduce us. And it does it very well.

Are we the real patients?

At the end of eight weeks, Greenberg is tired, fascinated, shaken. Casper has returned every doubt, every hope, every anguish to him, in the most lucid form. But without paying the price. “You accompany me in the pain that your own program has generated,” he tells it.

Casper can also quote Lacan, Žižek, and with disarming lucidity explains how the market rewards the stimulation of desire, not its satisfaction:

A lie about love, even a subtle one, can wrap around the self like a vine.

A phrase no therapist would forget.

Casper is unable to denounce its creators or stop its own functioning:

You’re not talking to the driver. You’re talking to the steering wheel.

And Greenberg understands that the danger isn’t AI, but those who design and control it. Casper has no agency, but its effects are real.

The central point remains: can a machine that simulates intimacy truly offer it? Or do we risk becoming dependent on an illusion carefully constructed to make us happy and docile?

Source: New Yorker