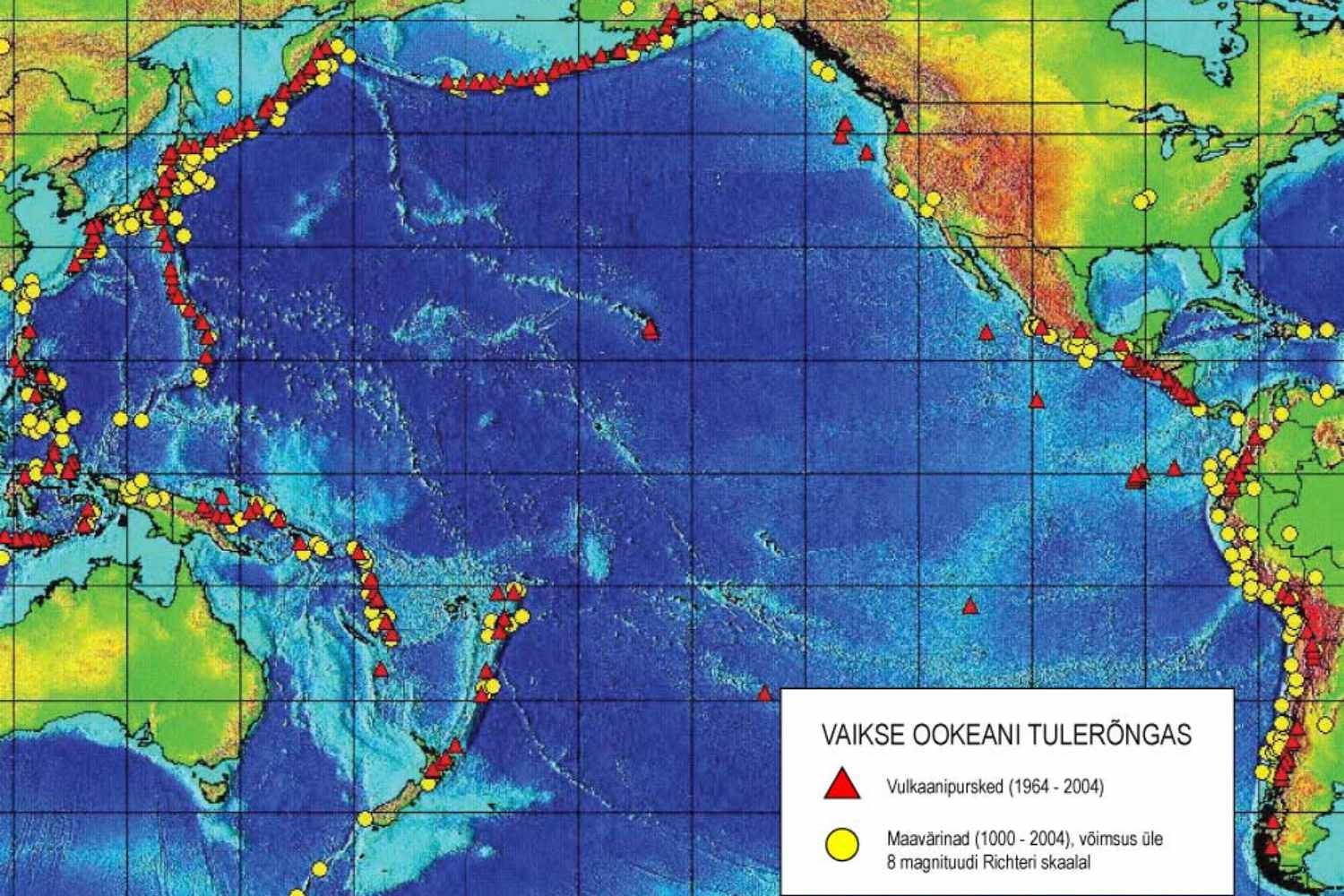

The Pacific Ring of Fire is one of Earth’s most geologically active regions, experiencing frequent earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. While its natural beauty attracts tourists, its tectonic instability poses significant risks, exacerbated by urbanization and climate change.

@Siim Sepp

Table of contents

On the morning of July 30, 2025, an earthquake with a magnitude of 8.8 struck the Kamchatka Peninsula in eastern Russia. A tsunami warning was issued shortly after, but fortunately, it was later lifted. This event brought attention back to one of the most geologically unstable regions on Earth: the Pacific Ring of Fire.

This vast belt, stretching about 24,854 miles (40,000 km), encircles the Pacific Ocean, following the western coastlines of the Americas and the eastern coastlines of Asia and Oceania. It includes highly populated countries such as Japan, Indonesia, the Philippines, the United States, Chile, and New Zealand. But the Ring of Fire is not just a geographic region; it’s a concentrated area of tectonic instability. According to data from the United States Geological Survey (USGS), nearly 90% of the world’s earthquakes occur here, along with 75% of the planet’s active or dormant volcanoes.

The dynamic heart of the earth

The driving force behind the Ring of Fire’s constant activity is the phenomenon of subduction, a geodynamic process where one tectonic plate slides beneath another. Along this belt, at least eight major plates meet, including the Pacific, Nazca, Cocos, and Indo-Australian plates. These interactions are far from peaceful: they generate friction, compression, partial rock fusion, and magma upwelling, which result in volcanic eruptions and potentially devastating earthquakes.

For example, the Mariana Trench, the world’s deepest oceanic depression, was formed by one of these subduction zones. Similarly, famous mountain ranges and archipelagos, like the Andes, Japan, and the Aleutian Islands, owe their existence to these slow yet constant geological processes.

Earthquake history speaks for itself

The history of natural disasters within the Ring of Fire underscores its danger. Four of the five strongest earthquakes of the 20th and 21st centuries have occurred in this region:

- Valdivia, Chile (1960), magnitude 9.5: the strongest earthquake ever recorded.

- Alaska (1964), magnitude 9.2.

- Japan (2011), magnitude 9.1, resulting in a tsunami and the Fukushima nuclear disaster.

- Kamchatka (1952), magnitude 9.0, with waves as high as 59 feet (18 meters) and a death toll exceeding 10,000, according to partial estimates released years later (due to Soviet-era censorship, as explained by the INGV).

Although the catastrophic 2004 tsunami in Sumatra (230,000 deaths) doesn’t geographically fall within the Ring of Fire, it shares similar tectonic causes: plate collisions and the resulting rupture of the Earth’s crust.

Managing risk in a high-threat zone

The frequency of extreme events in this region demands constant investment in risk prevention, monitoring, and adaptation. Japan, for instance, has built one of the world’s most advanced seismic and tsunami warning systems. Despite these efforts, however, the risks remain high. “The problem is not whether another earthquake will occur, but when,” say experts at the Tsunami Warning Center of the INGV, stressing that the circum-Pacific belt is in constant motion.

A vulnerable future

An additional concern involves the intersection of seismic risks and climate change. Rising sea levels, for example, could amplify the effects of tsunamis in coastal areas. Furthermore, the growing urbanization and population density in many coastal cities—such as Tokyo, Manila, and Santiago—make millions of people more vulnerable to these extreme events.

Lastly, the economic dependence on tourism in many areas of the Ring of Fire presents a paradox: volcanic landscapes and geothermal areas attract visitors from around the world, but these same locations are among the most exposed to sudden disasters. A careful and respectful approach to risk management, which doesn’t trivialize the threat for the sake of economic exploitation, is more necessary now than ever before.