Douglas Tompkins' life took him from the heights of business success to the depths of environmental conservation, leaving behind a legacy that continues to shape conservation efforts today.

@tompkins_conservation (IG)

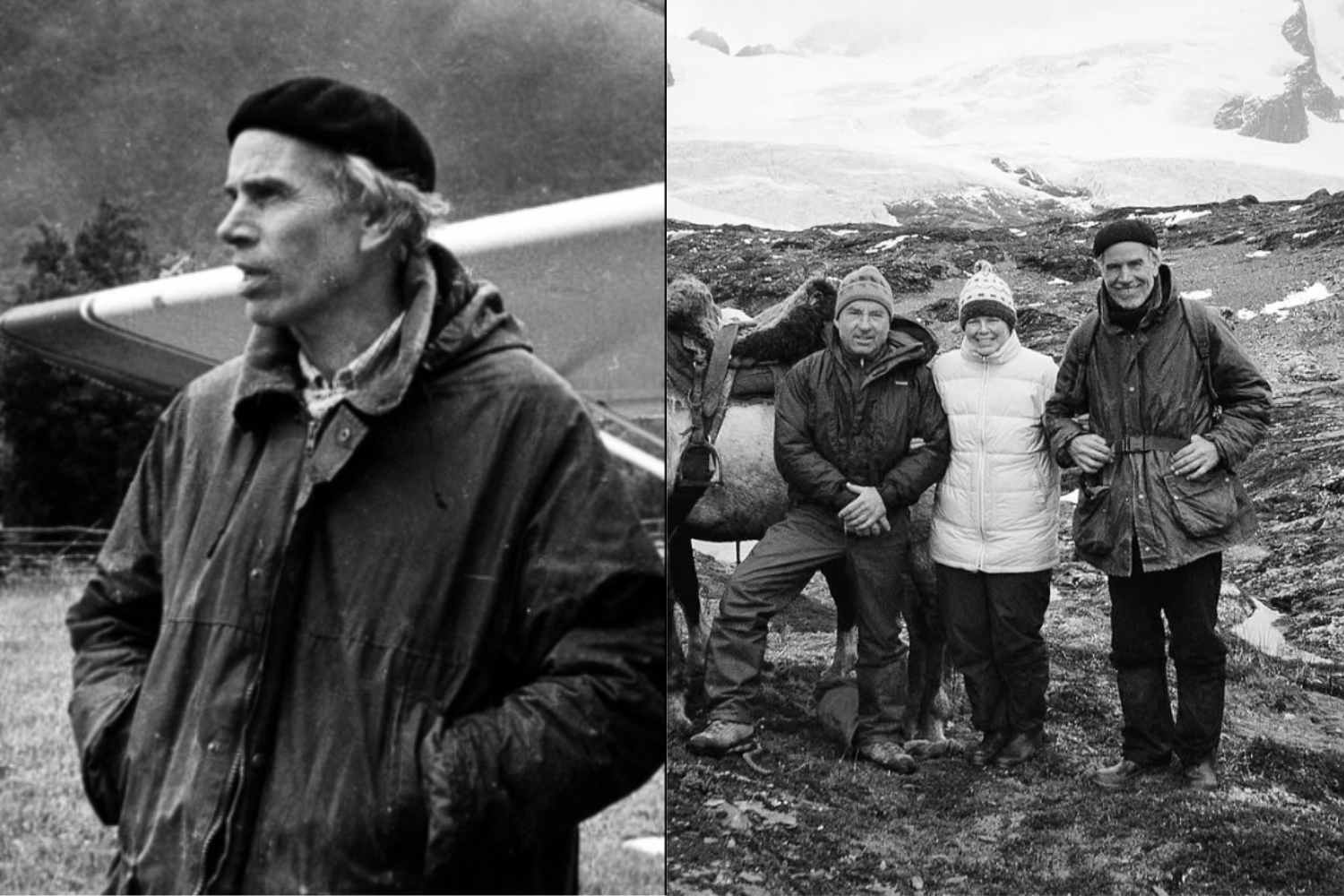

It almost feels like a tragic irony of fate. The man who built an empire on a love for the great outdoors, the co-founder of The North Face, Douglas Tompkins, met his end amid the forces of nature he had dedicated his second life to protecting. On December 8, 2015, the icy waters of General Carrera Lake in Chilean Patagonia rebelled, overturning his kayak and subjecting him to fatal hypothermia despite desperate rescue attempts. Yet, Tompkins’ biography doesn’t end at that lake. In many ways, it begins there.

His life was one of profound transformation: from a successful entrepreneur and icon of consumerism to one of the most influential and visionary conservationists of our time. A journey that led him to renounce the very system that had made him a billionaire, culminating in a declaration during a 2012 interview with Outside: “There is no doubt that there is no future in capitalism.”

From garage startup to crisis of conscience

Born in Ohio in 1943, Tompkins was a natural rebel. He dropped out of school to pursue his passions: skiing and climbing. In 1964, in San Francisco, he and his first wife Susie Buell founded a small shop selling ski and mountain gear. They named it The North Face, a name that was a declaration of intent. “The south face is the most climbed, the snow is softer, and the sunlight makes it warmer,” he once explained. “I prefer the tougher side. The icy, challenging north face. The North Face is a tougher challenge. That’s the road I take in life.”

The success was overwhelming, later replicated with the brand Esprit. But as profits grew, Tompkins felt an increasing sense of discomfort. He saw the world of business as a destructive machine. The turning point came in the late 1980s: he sold his shares, left the corporate world, and moved to South America. There, with his friend Yvon Chouinard, founder of Patagonia, he fell in love with the wild lands at the border of Chile and Argentina. It was here that he also met Kristine McDivitt, who was then the CEO of Patagonia. They married in 1993, uniting not only their lives but a common vision: to dedicate their wealth to safeguarding the planet.

The philosophy of deep ecology

Together, Doug and Kris launched one of the largest private conservation projects in history. They purchased nearly 890,000 acres (360,000 hectares) of land in Chile and Argentina. Their goal wasn’t to own, but to protect and give back. As Kristine explained, they were deeply influenced by Norwegian philosopher Arne Naess, the father of deep ecology. “At the heart of each of our parks,” she said, “is the belief that every form of life has intrinsic value.”

Their method was revolutionary. They bought old cattle ranches, such as the vast Estancia Valle Chacabuco, and began the process of rewilding: tearing down miles of fences, removing invasive plant species, and allowing nature to reclaim its space. This led to the return of native species like the guanaco, puma, condor, and huemul, the Andean deer. An immense effort, which resulted in the creation and expansion of national parks later donated to the Chilean and Argentine states. Among the jewels of their legacy are Pumalín Douglas Tompkins National Park and Patagonia National Park.

A legacy that continues to grow

The Tompkins’ work wasn’t without its obstacles. Initially, they were met with suspicion. Local politicians and businesspeople accused them of being “land grabbers” with hidden motives. But over time, the facts dispelled the doubts. Their collaboration with governments, culminating in a historic agreement in 2018 signed by Kristine and then-Chilean President Michelle Bachelet, led to the creation of a network of national parks protecting millions of acres.

After Doug’s death, Kristine Tompkins continued to lead their mission through Tompkins Conservation and its sister organizations, Rewilding Chile and Rewilding Argentina. Their work goes on with ambitious projects: the reintroduction of jaguars to the Iberá wetlands after 70 years of absence, the release of Andean condors, and the protection of the last kelp forests on the Mitre Peninsula.

Today, Douglas Tompkins rests in the Patagonia National Park cemetery, in the very land he so deeply loved and protected. As you exit, a sign reads a phrase that encapsulates his philosophy: “There is no synonym for God more perfect than beauty.” His life, a constant challenge against the current, proves that another way is possible and that true patriotism, as he said, is not about exploiting one’s country, but protecting it.