Jackson Pollock’s Number 1A, 1948 hides a secret: its electric blue is manganese blue, a rare synthetic pigment, now proven for the first time by MoMA and Stanford researchers.

©MoMa

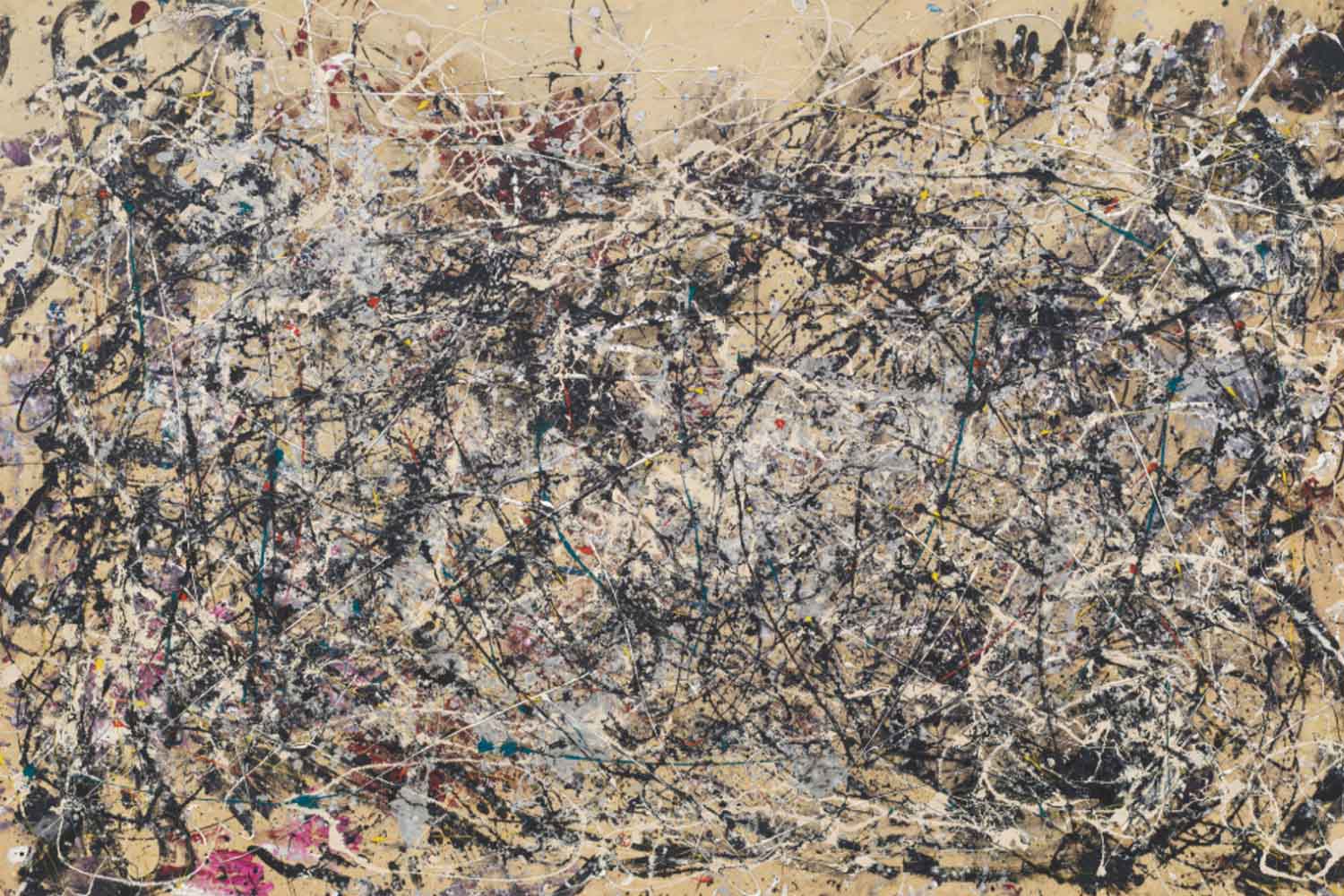

In a quiet corner of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, one of the most celebrated paintings of the 20th century continues to mesmerize its visitors. It’s called Number 1A, 1948, and it bears the unmistakable signature of Jackson Pollock, perhaps the most disruptive painter of his generation. But there is one detail that has always intrigued critics, artists, and scientists alike: that brilliant, almost electric blue flashing through the canvas like a bolt of lightning inside chaos.

For decades, nobody could say for certain what it was. Until now.

A pigment hidden in plain sight

A joint team from MoMA and Stanford University has finally identified the pigment. By removing microscopic paint samples from the canvas and examining them with Raman spectroscopy—a technique that uses laser light to read the vibrations of molecules—they discovered that Pollock had used manganese blue, a synthetic pigment invented in 1907 but only marketed in the 1930s.

Manganese blue had an almost mythical reputation among artists. It produced a radiant, crystalline turquoise, reflecting light in a way that natural pigments simply couldn’t. It absorbed both green and violet wavelengths, giving back to the human eye a blue that felt impossibly luminous. It wasn’t only for painters: in mid-century America it was also used in pool tiles and colored cement, prized for the way it held its brightness under the sun. But by the 1990s, the pigment had vanished from the market, discarded for environmental reasons.

As Edward Solomon, Stanford chemist and co-author of the study, explained:

“Understanding how such a powerful color works, at the molecular level, allows us to read the painting in a new way.”

Pollock didn’t know quantum chemistry, of course. But instinctively he understood that this pigment would create explosive visual contrasts on the canvas. He chose it because he knew it would make the painting breathe.

Proof at last

For years, scholars suspected manganese blue. Now, for the first time, its presence has been proven directly on the surface of the painting. Gene Hall, professor at Rutgers University, who conducted similar analyses on Pollock’s works in the past, confirmed from the outside:

“I’m convinced it really is manganese blue.”

The implications go beyond curiosity. Knowing the chemical makeup of pigments helps conservators predict how a painting will age—how it will respond to light, heat, or humidity. As Abed Haddad, MoMA chemist and co-author of the study, put it:

“We also work in layers, letting the materials speak. Exactly like Pollock did.”

The myth of chaos

The discovery sheds light not just on the pigment but on Pollock himself. The cliché of a painter working in pure chaos doesn’t hold up. Every drip, splash, and line was informed by deep knowledge of material and gesture. He rarely mixed colors; instead, he poured them directly onto the canvas, allowing each to remain distinct. That’s why scientists today can separate and identify them so clearly.

Look closely at Number 1A: black handprints scattered near the top, swift streaks of color laid down in a single motion, a fine white line cutting through the painting like an accident that is anything but accidental. And then that blue—so deliberate, so controlled, used not as decoration but as structure.

Pollock painted with his entire body. Gravity, density, speed—all were variables he managed with precision. His works were as much performance as they were painting, turning the floor into a stage of action.

Even the title Number 1A is telling. By avoiding narrative names, Pollock left interpretation open. The painting does not explain itself; it waits for the viewer to complete it.

Now, science has added one more piece to that interpretation. The blazing blue at its center, once mysterious, is revealed as the product of a rare and almost forgotten pigment. It doesn’t diminish the mystery—it deepens it, showing how instinct and chemistry conspired to give Pollock one of his most unforgettable colors.

Source: PNAS