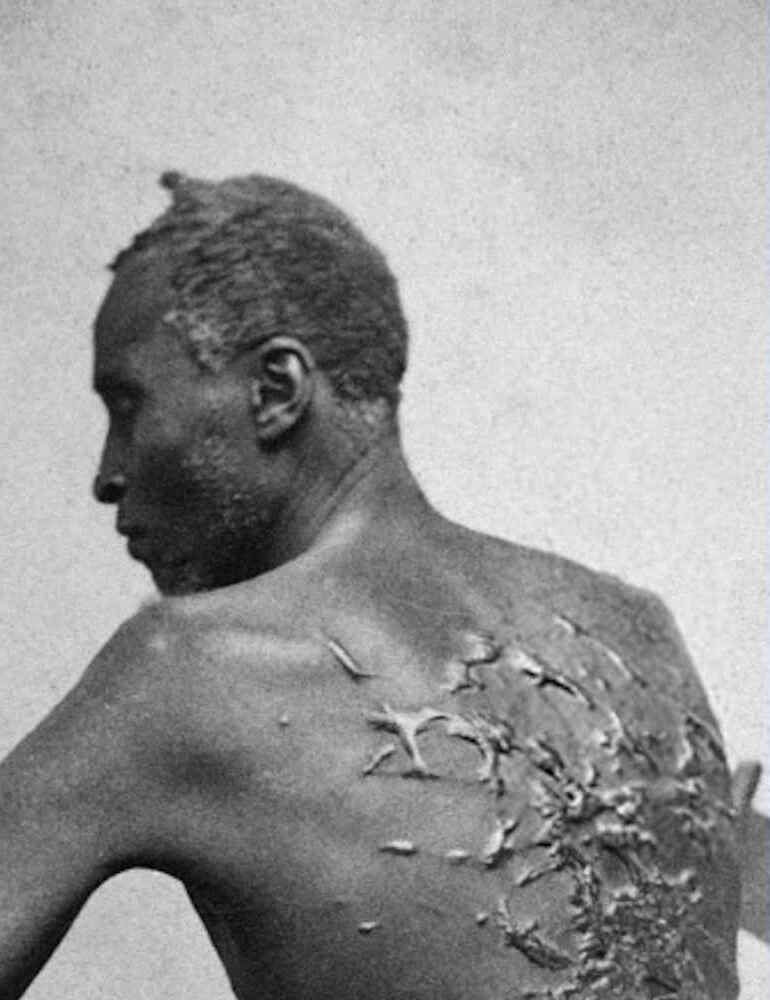

The 1863 photograph The Scourged Back captured the brutality of slavery and continues to resonate in American culture and politics.

A body marked by bruises, scars, and wounds. This is the image of a man known in history as Peter—or sometimes Gordon—a Louisiana slave, captured in 1863 in one of the most powerful and haunting photographs of the 19th century: The Scourged Back.

Reproduced and circulated thousands of times during the American Civil War, the photograph shook Northern consciences, where many people had never seen the brutal reality of slavery firsthand. For countless viewers, it became tangible proof of the systematic violence underpinning the institution of slavery, bolstering the abolitionist cause.

A story of escape and resistance

According to contemporary accounts, Peter managed to escape a cotton plantation in Louisiana in 1863. After days of walking, filthy and in tattered clothing, he reached Union lines, securing the freedom guaranteed by Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation.

His back, ravaged by whippings from the overseer, confined him to bed for months. Yet it was precisely those scars that became his most powerful testimony. In the photographic studio of William D. McPherson and J. Oliver, three versions of his portrait were taken. The third—showing the man’s profile most clearly—would become an icon of the fight against slavery.

The photograph that went “viral”

Printed as a carte de visite, a small-format, relatively inexpensive photograph commonly sold, shared, and exchanged by Civil War soldiers, the image spread quickly. It was sold, shared, and even mailed—a kind of pre-digital social media.

Abolitionist newspapers such as The Liberator used it to dismantle the pro-slavery propaganda that painted the system as “humane.” By July 1863, even the widely read Harper’s Weekly featured the portrait, bringing it to an even broader audience.

Historians note that it wasn’t Peter’s escape story that shocked the public so much, but the visual power of the image itself: a devastated back speaking louder than a thousand words.

A photo that still speaks (and Trump wants to censor)

More than 160 years later, Scourged Back continues to be displayed in American museums and universities, remaining a touchstone for reflection on the memory of slavery and its legacy. But not everyone is comfortable with it.

The image has been reinterpreted by artist Arthur Jafa in his sculpture Ex-Slave Gordon, appeared on the 2020 cover of The New Yorker in a collage dedicated to George Floyd, and inspired Viola Davis’s celebrated Vanity Fair portrait. In 2022, Peter’s story was also told in the film Emancipation, starring Will Smith.

In recent years, however, the photograph has become a political flashpoint. The Trump administration has moved to remove explanatory panels and entire exhibits deemed “noncompliant” or “denigratory,” following the March executive order Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History.

This measure affects exhibits covering crucial subjects such as slavery, the dispossession of Native peoples, and climate change. Among the works targeted is none other than the iconic 19th-century photograph, The Scourged Back.

Why “Scourged Back” still matters

This photograph is more than a historical document: it is a universal warning. It embodies the memory of millions enslaved and provides visual proof of systemic violence that shaped American society for centuries. Scholars remind us that it confirms photography’s power as a tool for justice and social change.

It forces us to confront the past in its harshness, rather than erase or sanitize it. Only by understanding this reality can we build a fairer future. To share images like Scourged Back is to remember, acknowledge, and honor the struggles that won the rights and freedoms we hold today. Historical memory is not optional—it is a collective duty.

Source: CCN