Mount Sinai’s St. Catherine’s Monastery, a UNESCO World Heritage site, faces drastic change as Egypt pushes a major tourism project, sparking protests from Bedouins and Greece.

@World Heritage Watch

Luxury hotels, sprawling villas and shopping complexes may soon rise around St. Catherine’s Monastery, the world’s oldest continuously inhabited Christian monastery. We are on Mount Sinai—Jabal Musa to locals—where the Egyptian government has unveiled an ambitious tourism development, complete with an expanded airport and even a cable car.

For centuries, visitors have reached the mountain’s summit with the help of Bedouin guides, climbing through the night to watch the sun rise over the rugged desert. Others came for guided treks into the valleys, always in the company of the local tribes. That experience, however, may soon look very different. The project’s name leaves little room for interpretation: The Great Transfiguration Project.

A world heritage site at risk

One of Egypt’s most sacred places, a UNESCO World Heritage Site that includes the monastery, the surrounding town and the mountain itself, could soon lose its unique character. Here, Jews, Christians and Muslims alike venerate the spot where—according to both the Bible and the Qur’an—Moses received the Ten Commandments and where God spoke to him from the burning bush. What has long been a landscape of silence and devotion could instead become a tourist hub, at the expense of the fragile desert ecosystem and the communities who have called this place home for centuries.

The bedouins displaced

For the Jebelaya tribe—the Guardians of St. Catherine—the story is already one of loss. According to BBC reports, their homes and fields have been demolished with little or no compensation. They were even forced to exhume their dead from the local cemetery to make way for a parking lot.

“This is not the kind of development the Jebeleya want or ask for,” says travel writer Ben Hoffler, who has long worked with Sinai’s tribes. “It is imposed from above to serve foreign interests, at the cost of the local community. A new urban world is being built around a traditionally nomadic tribe, a world they never consented to join, and it will forever change their place in their homeland.”

Greece enters the dispute

St. Catherine’s is not just the oldest Christian monastery still in use. It is also a living symbol of interfaith dialogue: next to the Byzantine basilica stands a small Fatimid mosque, evidence of centuries of coexistence between Christians and Muslims.

But that heritage is now caught in a diplomatic storm between Greece and Egypt. In May, an Egyptian court ruled that the monastery sits on state land, effectively limiting its rights to the main building and nearby archaeological sites. Athens reacted with outrage.

Archbishop Ieronymos II, head of the Church of Greece, denounced the ruling as “an outright expropriation.”

“This spiritual beacon of Orthodoxy and Hellenism is now facing an existential threat,” he declared.

Even Archbishop Damianos, who leads the monastery, described it as a “grave blow and a shame,” resigning amid divisions among the monks.

The Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem, which holds ecclesiastical jurisdiction over the site, reminded that St. Catherine’s has enjoyed special protection since antiquity, including a letter attributed to the Prophet Muhammad himself guaranteeing its safety.

Eventually, Greece and Egypt signed a joint declaration pledging to safeguard the monastery’s Greek Orthodox identity and cultural heritage.

Egypt’s “gift to the world”?

Launched in 2021, the Great Transfiguration Project envisions hotels, eco-lodges, a large visitor center, an expanded airport and a cable car to the summit. Cairo has promoted it as

“a special gift from Egypt to the entire world and to all religions.”

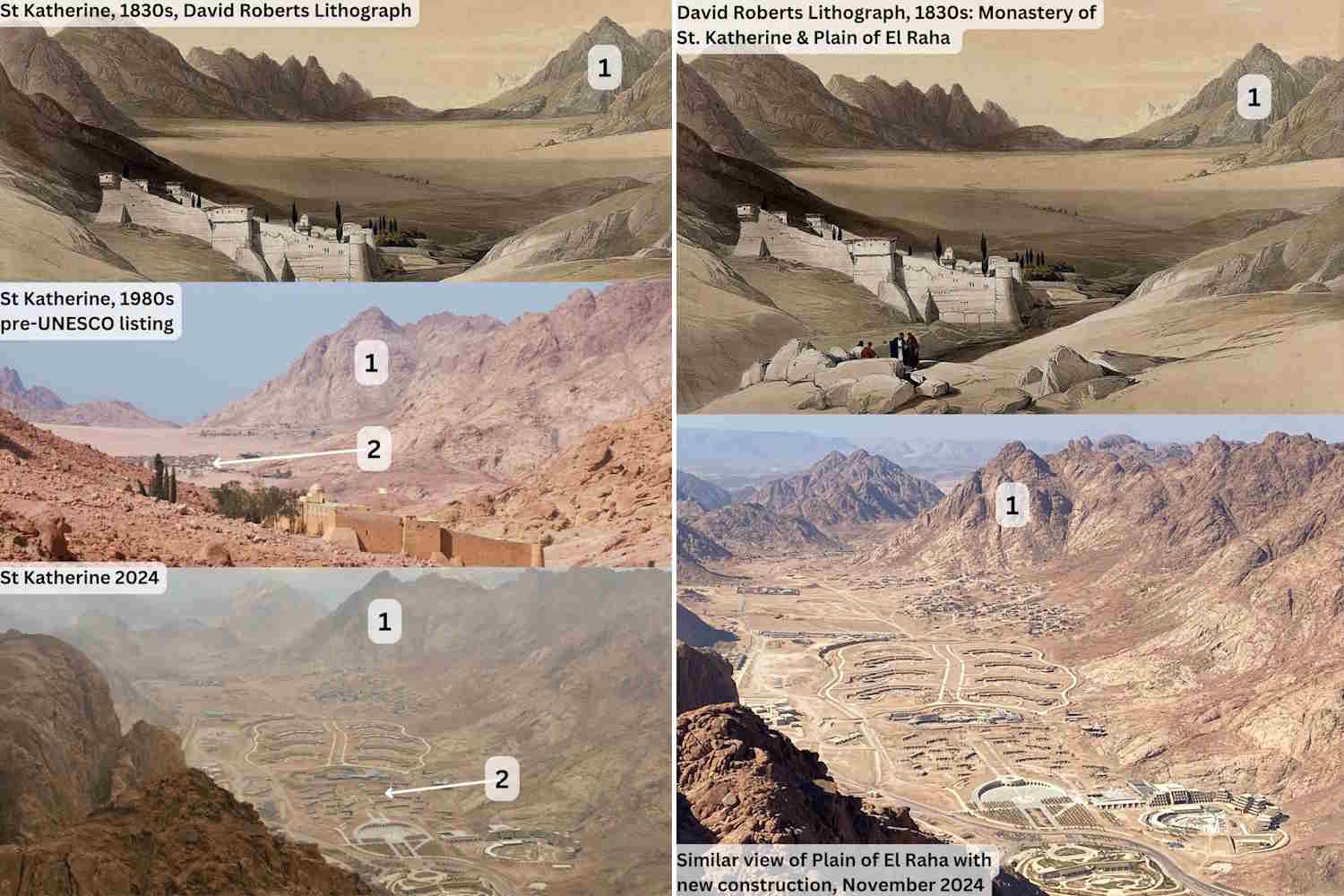

Yet progress has stalled, at least temporarily, due to funding shortages. Still, the Plain of el-Raha, which overlooks the monastery, has already been reshaped with new roads and construction zones.

UNESCO expressed concern in 2023, urging Egypt to halt the project, assess its impact and draft a conservation plan. No such plan has been delivered. In July, World Heritage Watch called on UNESCO to place St. Catherine’s on the List of World Heritage in Danger.

Tourism rises, bedouins left behind

Egypt’s tourism industry, battered first by the pandemic and now by the war in Gaza, is desperate to rebound. The government hopes to draw 30 million visitors by 2028.

For the Bedouins, however, this is a familiar story. Since the Sinai was returned to Egypt in 1979 after more than a decade of Israeli occupation, they have complained of being treated as second-class citizens. In the 1980s, resorts bloomed along the Red Sea in places like Sharm el-Sheikh, while the Bedouins were pushed aside.

Now, in St. Catherine’s, history risks repeating itself. A large hotel is already rising in the Plain of el-Raha, alongside smaller buildings altering the valley’s appearance. Once again, the construction workforce comes mostly from elsewhere, while locals are left with vague promises of “upgraded” housing.

For centuries, St. Catherine’s Monastery has been a spiritual refuge, home to the Codex Sinaiticus—the world’s oldest nearly complete copy of the New Testament—and to the burning bush revered in both the Bible and the Qur’an. But the silence, the Bedouin identity, the sense of timeless isolation—those could soon be gone forever.

Sources: BBC / World Heritage Watch