Even when Earth is farthest from the Sun, July brings extreme heat. Here's why the planet’s tilt matters more than distance in shaping our seasons.

Yesterday, Thursday, July 3, 2025, at 3:54 p.m. EDT / 12:54 p.m. PDT, something quiet and cosmic happened. Earth reached its aphelion, the point in its orbit where it’s farthest from the Sun. To be precise, we were about 94.5 million miles away (that’s 152,087,738 kilometers), nearly 3.1 million miles farther than we are in early January during perihelion, when Earth is closest to the Sun.

Sounds like we should be freezing, right?

Not even close. Depending on where you live in the Northern Hemisphere, you’re probably sweating through some of the hottest days of the year. This isn’t some celestial contradiction—it’s a brilliant reminder that distance isn’t everything when it comes to climate.

Why we burn even when we’re farther away

The reason we’re sizzling in the heat isn’t about how far we are from the Sun. It’s about how tilted we are.

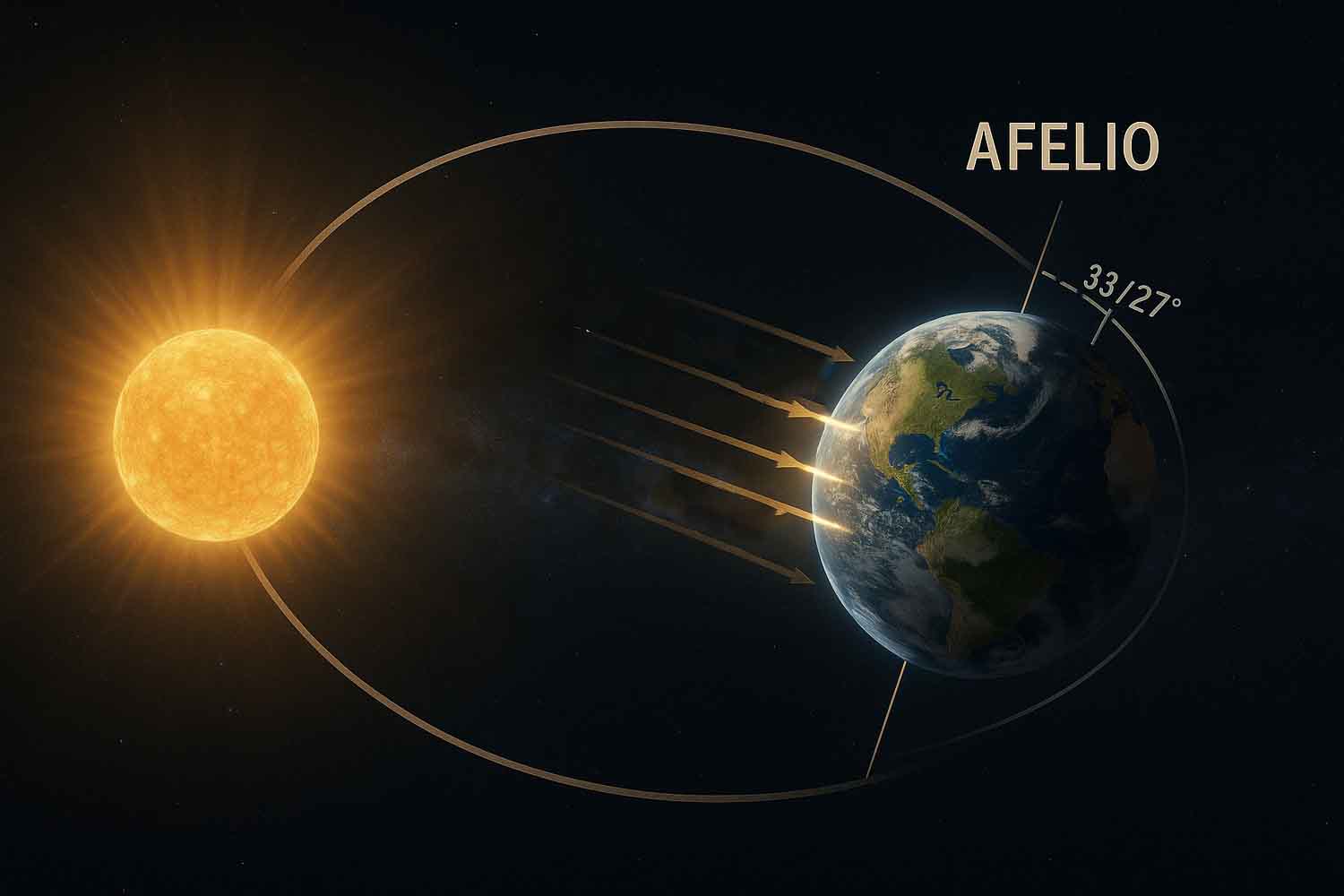

Earth’s axis is tilted by about 23.5°, and that tilt changes everything. It’s the real engine behind the seasons, not our planet’s elliptical path around the Sun. Sure, Earth’s orbit isn’t a perfect circle—it’s an ellipse, just as Kepler’s First Law describes. That means the distance between Earth and the Sun varies throughout the year, and during aphelion, we’re at our orbital max.

Interestingly, the Sun doesn’t sit in the center of this ellipse, but at one of the focal points, which is why there’s such a clear gap—about 3.1 million miles (4.94 million kilometers)—between the closest and farthest points in our orbit. That’s a 3.5% difference from the average Earth-Sun distance, which is roughly 92.96 million miles (149.6 million km).

Even so, this extra distance only reduces solar energy by around 6.5%. And though other planets exert minor gravitational pulls that can nudge Earth’s orbit a bit year-to-year, none of it really impacts our seasons.

So, why is it hot now?

Because our hemisphere is tilted directly toward the Sun. During the Northern Hemisphere’s summer, sunlight hits us more directly. The Sun’s path across the sky is longer and higher, meaning we get more daylight hours, and the energy per square foot is much greater.

Even with that slight 6.5% dip in energy due to distance, the Sun’s high angle and long exposure time easily compensate. In fact, across mid-latitudes, the solar energy per square foot can vary by up to 250% between winter and summer. That’s massive.

It’s not about proximity. It’s about the angle.

That explains why July—right at aphelion—is still one of the hottest months of the year in many places. The Sun isn’t “weaker.” It’s just working smarter, blasting us straight on rather than from a low slant.

So next time you’re sweating in the July heat and someone mentions we’re farther from the Sun than any other day of the year, just nod and say: “Yeah, but the Sun’s aiming straight at us.”

Source: NASA