Hawaii is inching toward Japan at 4 inches per year due to Pacific Plate movement. A stunning example of how tectonics shape our world—just don't expect a collision anytime soon.

The Hawaiian Islands, famous for their lush landscapes and fiery volcanoes, are part of a slow-motion geological journey—one that’s been unfolding for millions of years and will continue long after we’re gone. They are, quite literally, moving closer to Japan.

This isn’t a metaphor or a poetic flourish. It’s plate tectonics in action.

The slow dance of the pacific plate

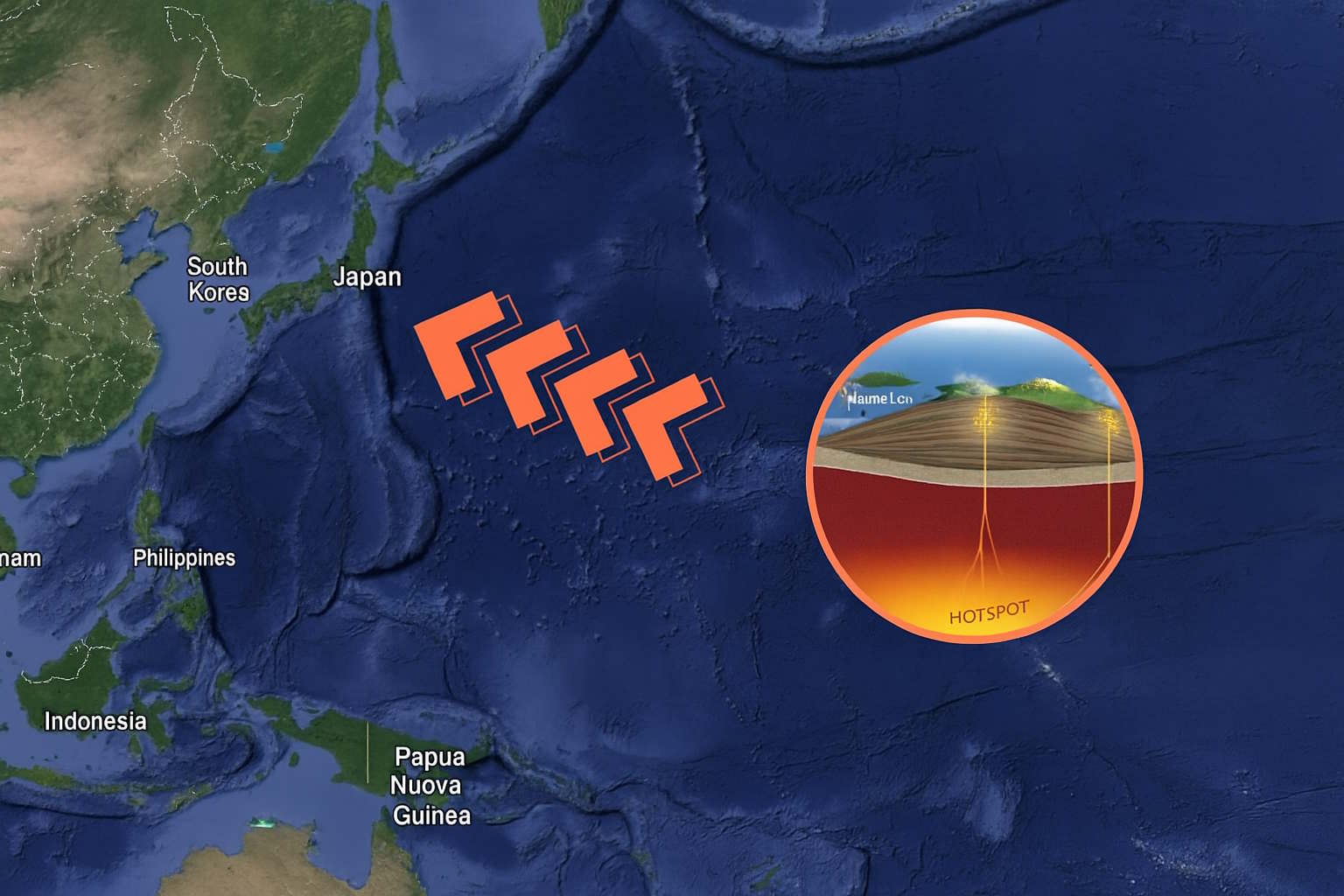

The Hawaiian archipelago sits on the Pacific tectonic plate, the largest of Earth’s tectonic divisions. Each year, this plate shifts northwest at a pace of about 4 inches (10 centimeters). That might not seem like much—it’s less than the length of your average smartphone—but on a geological timescale, it’s a steady march with dramatic implications.

This northwest drift means Hawaii is inching its way across the Pacific Ocean, heading—very slowly—toward Japan.

Born from fire, moved by force

The islands themselves are volcanic creations, born from a “hotspot” deep within Earth’s mantle. This hotspot doesn’t move. Instead, it’s the Pacific Plate that glides over it, and as it does, new islands form over the hotspot while older ones drift away and begin to erode.

That’s why Big Island (Hawai‘i), currently above the hotspot, is the youngest and most volcanically active of the Hawaiian Islands. As the plate slides, another island will eventually rise from the sea to take its place.

It’s a process that constantly reshapes Earth’s surface, offering a dramatic reminder that the ground beneath us is anything but still.

Understanding the stakes — and the timeline

Let’s be clear: no one in Tokyo is preparing to greet Hawaiian tourists by foot. The full journey from Hawaii to Japan spans roughly 3,850 miles (6,200 kilometers). At the current pace, scientists estimate it would take around 63 million years before the two come into any real contact.

“Sixty-three million years”—let that number sink in. By then, our species may be long gone, and new landmasses might have risen and fallen. So, no, this isn’t a warning. It’s a window into the deeper workings of our planet.

The science behind the shift

This long-term drift is a tangible result of the theory of plate tectonics—the idea that Earth’s rigid outer shell (the lithosphere) is broken into plates that float atop the softer, more fluid layer beneath, known as the asthenosphere.

This theory explains earthquakes, volcanic activity, and the formation of mountain ranges. And it’s far from just academic. By studying how plates like the Pacific Plate move, geologists gain valuable insights into future seismic risks and volcanic behavior, especially in high-risk zones like Hawaii.

A moving planet, a living world

What makes this slow-motion journey so captivating isn’t just the movement itself—it’s what it represents. Earth is a dynamic, living planet, constantly reshaping itself. What looks solid is, over the vast sweep of time, fluid.

And while this may not change your travel plans or threaten coastal cities in our lifetime, it reminds us of a crucial truth: we are passengers on a planet in motion, and the story beneath our feet is far older—and far stranger—than we often remember.

Source: US Geological Survey