A study from the University of California reveals that queen bumblebees take regular breaks during reproduction to prevent burnout, highlighting the complexity of their reproductive strategies.

Canva

A study led by the University of California (USA) reveals that queen bumblebees take regular breaks during reproduction, likely to avoid burnout before the worker bees arrive. This behavior highlights the complex balancing act these bees perform as the foundation of their colonies.

What bumblebees are and why they’re important

As explained by the Museum of Zoology at Sapienza University of Rome, bumblebees belong to the bee family and are notable for their large size, loud buzz, and bright appearance. They play an essential ecological and commercial role as pollinators, especially in temperate regions.

Interestingly, bumblebees have a wide distribution, ranging from Arctic to temperate zones, and even tropical areas. This is thanks to their ability to regulate body temperature through an internal “vibration” mechanism that generates heat, as well as a cooling system that works by radiating heat from their abdomens.

However, like many other pollinators, bumblebees are facing severe threats due to climate change, pollution, habitat loss, and intensive farming. It’s not just honeybees that are suffering—bumblebees are also in decline.

In 2021, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed the American bumblebee (Bombus pensylvanicus) among the three species requiring further study for potential inclusion in the Endangered Species List. It was estimated that the population of this species had dropped by 89% since 2002. While it was once found in 47 out of 48 continental U.S. states, by 2021 it had disappeared from at least eight (Maine, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont, Idaho, North Dakota, Oregon, Wyoming). In New York alone, the population had dropped by 99%, and in the Southeast and Midwest regions, declines exceeded 50%.

And no, the situation has not improved since then.

©BMC Ecology and Evolution

In the early stages of colony formation, queen bumblebees must juggle numerous responsibilities: they forage for food, care for developing larvae by warming them with their wing muscles, tend to the nest, and lay eggs. It’s a high-risk balancing act; without the queen, the colony fails.

Yet researchers have observed an intriguing rhythm: a burst of egg-laying followed by several days of apparent inactivity.

“I first noticed these breaks right from the start, simply by taking daily photos of the nests,” says Blanca Peto, lead author of the new study. “It wasn’t something I expected, so I wanted to understand what was happening during those pauses.”

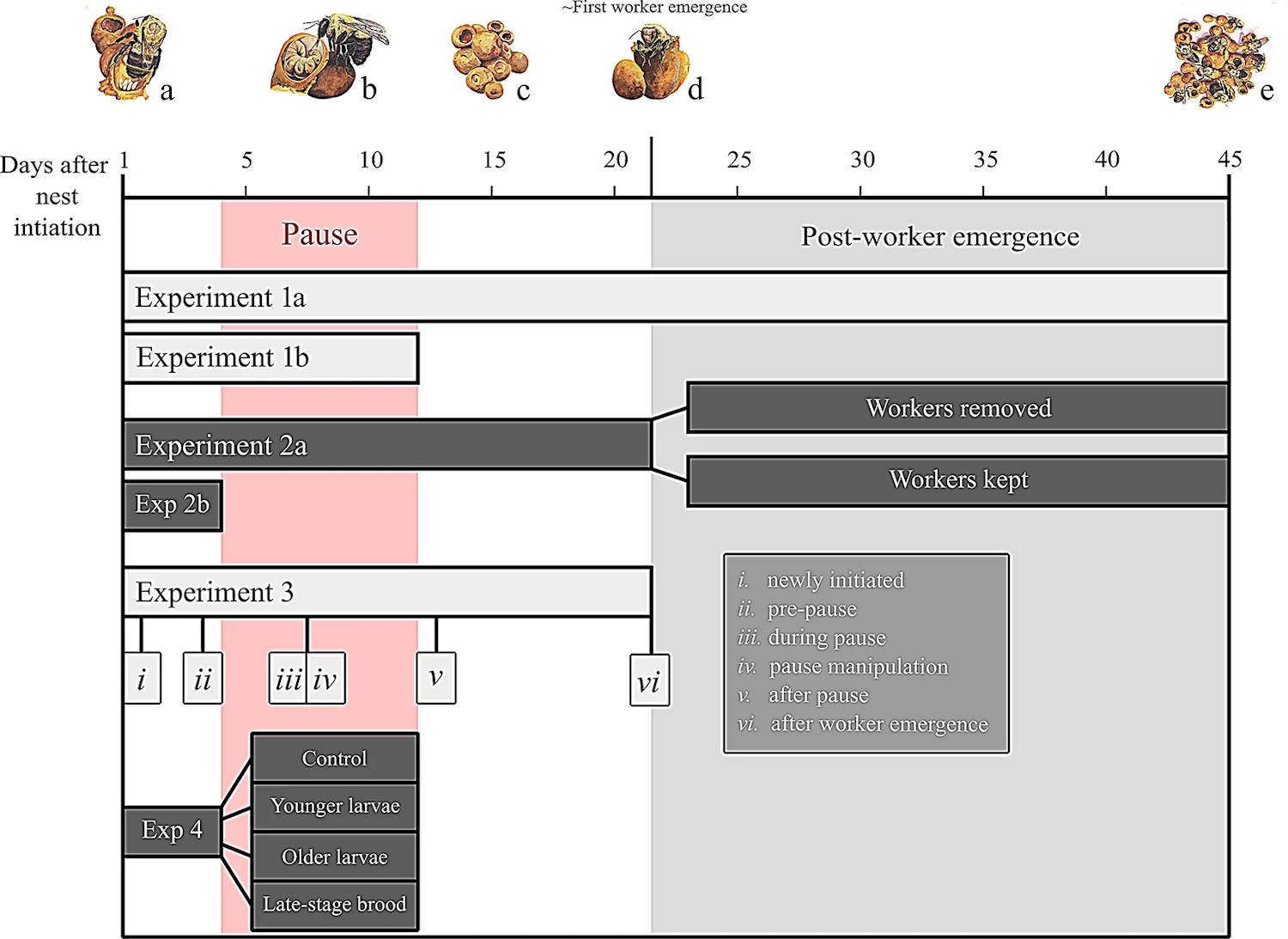

To uncover what triggers these breaks, Peto monitored over 100 queens for 45 days in a controlled insectarium, documenting each queen’s nesting activity and observing their distinctive broods—groups of eggs laid in wax-covered “cups” surrounded by pollen mounds.

The first observation was clear: across the population, many queens paused reproduction for several days, typically after a period of intense egg-laying. And these breaks seemed to coincide with the developmental stages of the existing brood.

To verify this, Peto experimentally added larvae at different stages—young larvae, older larvae, and pupae—during the queen’s natural break. The presence of pupae, nearly-adult insects, prompted queens to resume egg-laying within about 1.5 days. In contrast, without additional broods, the breaks extended to an average of 12.5 days.

This suggests that queens respond to signals from their developing offspring and schedule their reproductive efforts accordingly.

“There’s something in the presence of pupae that signals it’s safe or necessary to start laying again,” explains Peto. “It’s a dynamic process, not a constant production as we once thought.”

The dynamic reproductive behavior of bumblebee queens

Eusocial insects, including bumblebees, have overlapping generations, cooperative brood care, and division of labor. Until now, it was assumed that such insects reproduced continuously at all stages of development. However, this study challenges that conventional view of bumblebees, showing that their reproductive behavior is much more nuanced and intermittent.

“This study demonstrates that the queen’s reproductive behavior is far more flexible than we previously thought,” says Peto. “This is crucial because those early days are incredibly vulnerable. If a queen pushes too hard and too fast, the whole colony could fail.”

While the study focused on a single species native to the eastern United States, the implications could extend to other bumblebee species or even other eusocial insects. Queens of other species may also slow down their pace during the early stages of nest founding. If that’s the case, this innate rhythm could be an evolutionary trait that helps queens survive long enough to build a workforce.

Bumblebee populations in North America are declining

Several bumblebee populations in North America are declining, primarily due to habitat loss, pesticide exposure, and climate stress. Understanding the biological needs of the queens, the literal foundation of each colony, could help environmentalists better protect them.

“Even in a lab where everything is stable and they don’t have to forage for food, queens still pause,” says Peto. “This tells us that it’s not just a response to stress, but something fundamental. They are managing their energy in an intelligent way. Without queens, there is no colony. And without colonies, we lose essential pollinators. These interruptions could be the real reason for the success of the colonies.”

The study was published in BMC Ecology and Evolution.

Sources: University of California / BMC Ecology and Evolution